Federalization of the National Guard & Domestic Use of Federal Forces

Date of Information: 06/08/2025

Please check back soon; we update these materials often.

The deployment of military forces within the United States—particularly the federalization of the National Guard—raises fundamental questions about civilian control of the military, sovereignty of the state and federal governments, and the lawful limits of executive power. This article outlines the legal framework governing federalization, explores its intersection with the Posse Comitatus Act, and provides a practical guide to the lawful domestic use of federal forces in support of civil authorities.

Two Distinct but Interrelated Legal Questions

Any legal assessment of the domestic use of military forces—including the federalization of the National Guard—must begin with an understanding of two separate but overlapping legal authorities:

1. The President’s Authority to Commandeer Forces Normally Under State Control

The National Guard is unique among U.S. military forces in that it exists under dual sovereignty. While ordinarily under the command of the state governor (Title 32 status), the President has statutory authority to bring these forces under federal control (Title 10) under limited circumstances.

This authority derives from 10 U.S.C. § 12406 and the Insurrection Act (10 U.S.C. §§ 251–253).

When federalized, Guardsmen become indistinguishable from active-duty personnel and are subject to all restrictions applicable to federal troops—including the Posse Comitatus Act.

Federalization effectively removes a governor's command authority, transferring operational control to the President. This can be lawful, but only under conditions clearly articulated by statute.

2. The President’s Authority to Employ Federal Forces Domestically to Support Civil Authorities

Even when military forces are already under federal control—such as the active-duty Army, Air Force, Navy, or Marines—their deployment on U.S. soil for law enforcement or domestic order operations is heavily restricted.

The Posse Comitatus Act (18 U.S.C. § 1385) generally bars federal troops from engaging in domestic law enforcement.

The principal statutory exception is the Insurrection Act, which permits such deployments only in response to rebellion, obstruction of law, or threats to constitutional rights that state governments cannot or will not suppress.

Thus, even if the President lawfully federalizes National Guard forces, their actual use domestically must also satisfy separate legal criteria. Misunderstanding or conflating these two questions—who controls the force, and what the force is legally permitted to do—can result in serious constitutional violations.

Legal Framework for Federalization and Domestic Deployment

The National Guard functions under a dual federal-state structure defined by the U.S. Code:

State Control (Title 32, U.S. Code)

Under 32 U.S.C. § 502(f), National Guard personnel typically serve under the command of state governors.

32 U.S.C. §§ 901–908 authorizes federally funded but state-controlled deployment for domestic missions, such as disaster relief and law enforcement support.

Federal Control (Title 10, U.S. Code)

The President may federalize the Guard in several circumstances:

10 U.S.C. § 12406 allows for activation to repel invasion, suppress rebellion, or execute federal law.

The Insurrection Act (10 U.S.C. §§ 251–253) provides broader authority to deploy federal forces—including the National Guard—when a state is unable or unwilling to manage insurrection or enforce constitutional rights.

These statutes define the limits and responsibilities of both state and federal authorities.

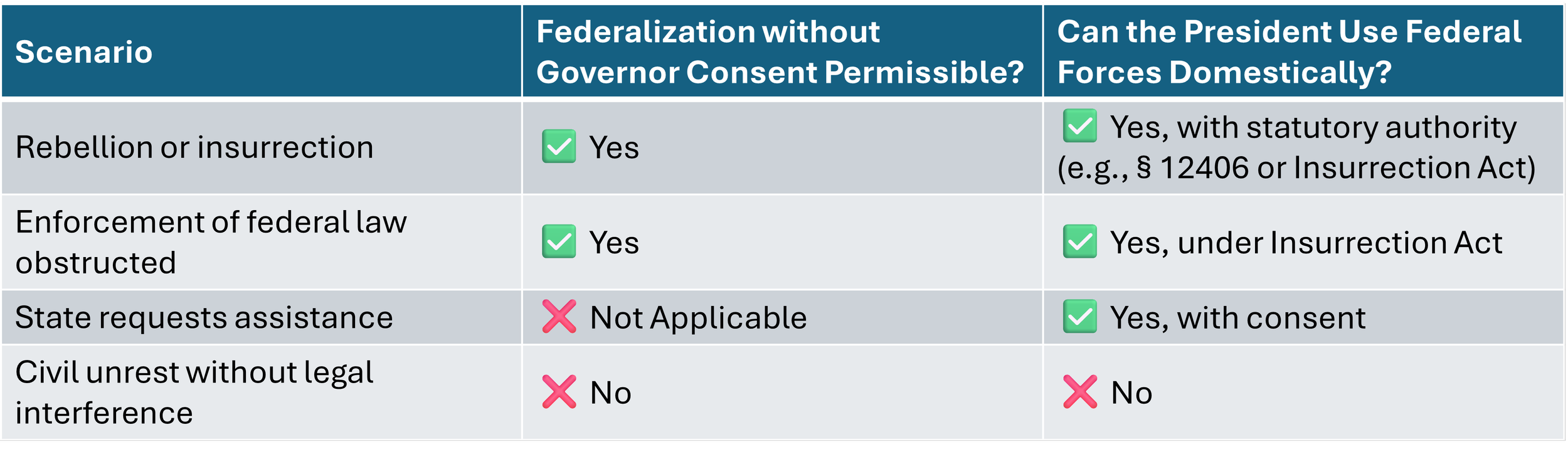

Comparison of Domestic Military Authorities

Historical Invocations of Federalization and Domestic Force

Throughout American history, the federalization of the National Guard and the deployment of federal forces on U.S. soil have occurred during moments of profound domestic conflict or crisis. These precedents underscore both the gravity and the rarity of such actions:

1. Whiskey Rebellion (1794)

Although predating the current statutory framework, President George Washington invoked the similar Militia Acts of 1792 to federalize state militias and suppress a violent tax protest in western Pennsylvania. It marked the first time federal forces were used to enforce national law domestically.

2. Civil War Era (1861–1865)

President Abraham Lincoln repeatedly invoked emergency military powers to preserve the Union. Though the Insurrection Act was not yet codified in its modern form, he relied on inherent Article II powers and early statutory frameworks to deploy troops domestically without state consent.

3. Reconstruction (1866–1877)

Federal troops were stationed throughout the South to enforce civil rights protections and suppress paramilitary resistance. The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 was passed at the end of this era to limit future domestic use of federal troops, reflecting a backlash against prolonged military governance.

4. Little Rock, Arkansas (1957)

President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard under 10 U.S.C. § 12406 and deployed the 101st Airborne Division to enforce school desegregation following defiance of federal court orders. This action relied explicitly on the Insurrection Act.

5. Detroit Riots (1967)

During widespread civil unrest, President Lyndon B. Johnson invoked the Insurrection Act and deployed federal troops to Detroit after the governor’s request, illustrating the typical model of cooperative federalization.

6. University of Mississippi (1962)

President John F. Kennedy used federalized Guard forces and active-duty troops to enforce a court order admitting James Meredith, the university’s first Black student. The resistance was deemed a rebellion under the Insurrection Act.

7. Los Angeles Riots (1992)

President George H. W. Bush federalized over 4,000 National Guard troops and deployed nearly 2,000 active-duty soldiers and Marines in response to the Rodney King verdict riots. The California governor formally requested the assistance.

8. Hurricane Katrina (2005)

While active-duty troops were deployed for humanitarian response, federalization was avoided. President George W. Bush and Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco disagreed over whether to transfer control of the Louisiana National Guard, highlighting political and legal sensitivities around Title 10 activation.

These examples demonstrate that federalization and domestic use of military force typically fall into three categories:

To enforce federal court orders and civil rights protections.

To respond to violent insurrections or rebellion.

To support overwhelmed state authorities upon request.

In each case, legal authority was matched with either compelling factual necessity or gubernatorial consent, or both. These precedents reinforce the principle that such actions should remain exceptional, deliberate, and firmly rooted in law.

When Domestic Deployment Is Legally Permissible

Federalization and domestic military deployment are legally valid only under certain conditions. The table below summarizes key scenarios:

Strategic Considerations for Domestic Use of Federal Forces

The domestic use of military power must always be approached with caution. Strategic implications include:

Preserving federalism through preference for Title 32 operations, which maintain state control.

Avoiding escalation by ensuring Title 10 federalization is grounded in clear necessity.

Recognizing that the Insurrection Act authority is a tool of last resort.

Domestic use of force should always align with public safety, constitutional integrity, and civilian oversight principles.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does it mean to “federalize” the National Guard?

Federalization occurs when the President transfers National Guard units from state control (Title 32) to federal control (Title 10). Once federalized, Guardsmen are treated as active-duty military subject to federal restrictions like the Posse Comitatus Act.

2. Can the President deploy federal troops inside the United States?

Yes, but the Posse Comitatus Act generally prohibits federal forces from domestic law enforcement unless a statutory exception—most notably the Insurrection Act—applies.

3. What is the Insurrection Act, and when can it be used?

The Insurrection Act (10 U.S.C. §§ 251–253) allows the President to use federal forces to suppress rebellion, enforce federal law, or protect constitutional rights when states cannot or will not act.

4. What’s the difference between Title 32 and Title 10 status for the Guard?

Under Title 32, the Guard remains under state governor control but may receive federal funding. Under Title 10, Guardsmen are under federal command, indistinguishable from active-duty forces.

5. Does federalization remove a governor’s authority?

Yes. When Guard forces are federalized, governors lose command authority, and the President assumes operational control.

6. Has federalization been used before?

Yes. Historical examples include Little Rock (1957), the Detroit riots (1967), integration of the University of Mississippi (1962), and the Los Angeles riots (1992).

7. Can the President federalize the Guard without a governor’s request?

Yes, but this is highly sensitive. While federal law permits it in cases of insurrection or obstruction of federal law, most federalizations historically involved either state requests or court order enforcement.

8. What are the limits on using federalized forces domestically?

Even when lawfully federalized, their use is restricted. Federal forces cannot engage in domestic policing unless authorized by statute, and actions must be narrowly tailored to the crisis at hand.

9. How does federalization affect civil liberties?

Improper or excessive use risks eroding constitutional rights, politicizing the military, and undermining federalism. Safeguards like congressional oversight and judicial review help maintain balance.

10. Why is reform of the Insurrection Act being debated today?

Because its broad language creates risk of misuse. Legal scholars and policymakers recommend clarifying thresholds, requiring congressional notification, and ensuring deployments remain exceptional.

Conclusion

The federalization of the National Guard and the use of federal forces within the United States must be tightly circumscribed by law. Actions taken outside these legal parameters risk eroding civil liberties, politicizing the military, and upsetting the federal balance of power.

Policy recommendations include:

Modernizing the Insurrection Act with clearer thresholds and procedural safeguards;

Strengthening congressional oversight of domestic deployments; and

Reinforcing the principle that civil authority in the homeland must remain primarily civilian, not militarized.