U.S. Customs and Border Protection:

Mission, Structure, Authorities, and Legal Limits

Date of Information: 08/17/2025

Check back soon; we update these materials frequently

Introduction

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) plays a central role in enforcing the nation’s immigration and customs laws at and near the border. As the primary line of defense at ports of entry and along the nation's borders, CBP wields unique legal authorities that distinguish it from other law enforcement agencies—powers that include warrantless searches, expedited removals, and jurisdiction over a broad geographic area extending up to 100 miles into the interior. But these powers are not without constitutional and statutory limits. This page provides a detailed overview of CBP’s mission, legal framework, jurisdictional boundaries, and its relationship to other immigration enforcement entities, particularly U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). It is intended as a resource for understanding both what CBP is authorized to do and where its authority stops.

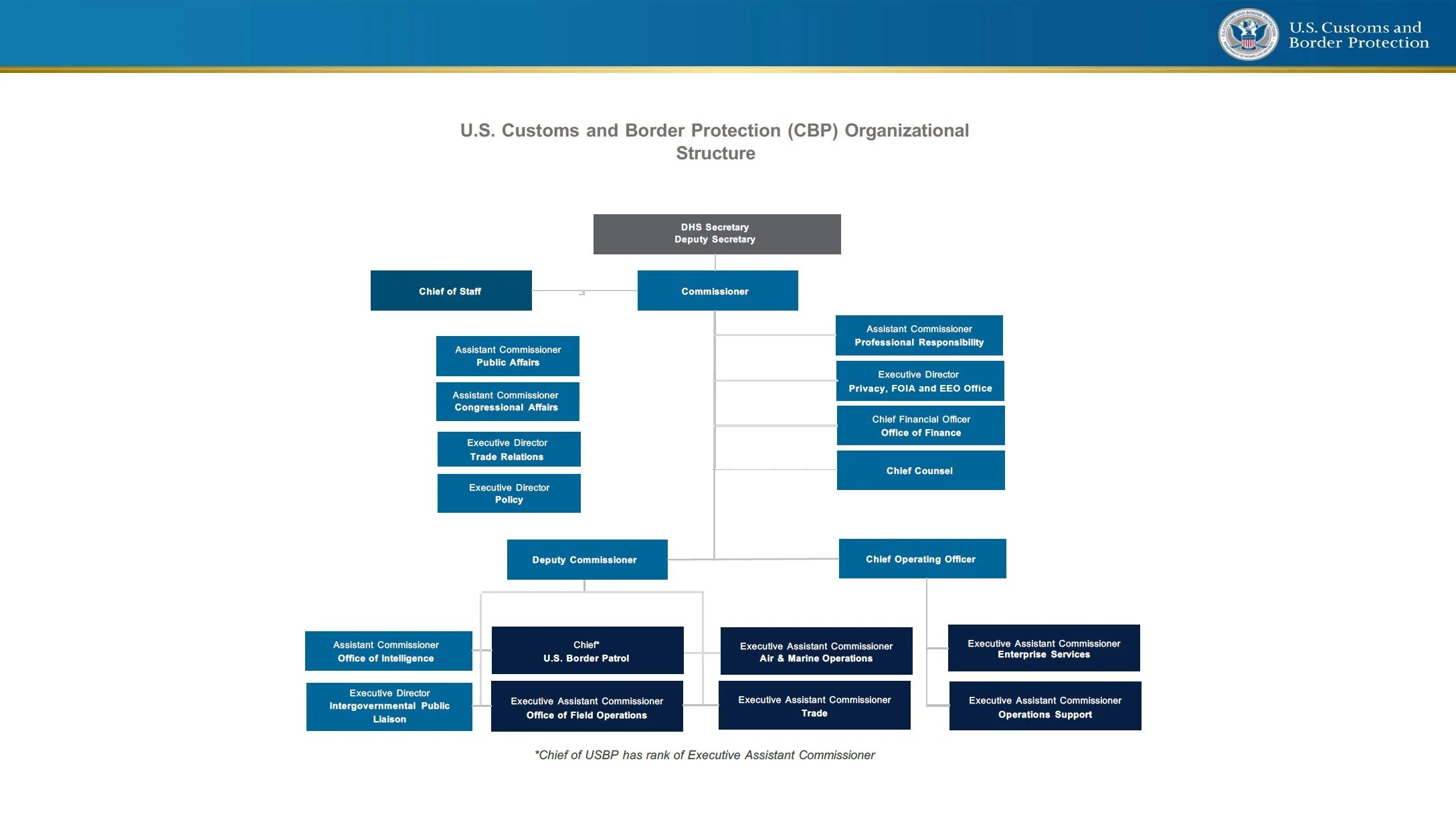

I. Mission and General Organization of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

CBP is one of the largest law enforcement agencies in the United States, with a workforce of over 60,000 employees. Its personnel include Border Patrol agents, Air and Marine officers, and customs officers stationed at ports of entry. The agency is responsible for screening individuals and goods at the border, enforcing immigration and customs laws, and safeguarding agricultural interests.

Key Missions:

Prevent unlawful entry of people and contraband

Facilitate legitimate trade and travel

Enforce customs, immigration, and agricultural laws

Support counterterrorism and national security operations

CBP is divided into several major operational branches:

Office of Field Operations (OFO) – Operates at official ports of entry

U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) – Patrols areas between ports of entry

Air and Marine Operations (AMO) – Provides aerial and maritime surveillance and interdiction

II. Unique Law Enforcement Authorities of CBP

CBP possesses special statutory and regulatory powers that distinguish it from most other federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. These authorities are derived primarily from the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), Title 8 of the U.S. Code, and Title 19 (customs enforcement).

Key Special Authorities:

Search Authority Without Warrant or Probable Cause: CBP may conduct warrantless searches of persons, vehicles, and belongings at the U.S. border and its functional equivalent. (United States v. Ramsey, 431 U.S. 606 (1977)).

100-Mile Border Zone: CBP may operate within a 100-air-mile radius of any external U.S. boundary, per 8 C.F.R. § 287.1(a)(2), including checkpoints and patrols.

Immigration Checkpoints: CBP may stop vehicles at fixed checkpoints without individualized suspicion, consistent with the Fourth Amendment. (United States v. Martinez-Fuerte, 428 U.S. 543 (1976)).

Roving Patrols: CBP may stop vehicles only if agents have reasonable suspicion of an immigration violation or crime. (United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U.S. 873 (1975)).

Electronic Device Searches: See Section VI below for full detail.

III. Legal and Constitutional Constraints on CBP

Despite these broad authorities, CBP is subject to significant constitutional and statutory limits.

Notable Limitations:

No General Police Power: CBP cannot enforce state criminal law unless specifically authorized or acting under intergovernmental agreements. See Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387, 408–10 (2012) (holding that immigration enforcement is a federal power and rejecting state efforts to criminalize unauthorized presence).

Fourth Amendment Protections: The border search exception applies at the border and its functional equivalents but does not override all privacy rights. See United States v. Montoya de Hernandez, 473 U.S. 531, 538 (1985) (recognizing a reduced expectation of privacy at the border, but still requiring reasonableness under the Fourth Amendment).

Limitations Within the 100-Mile Zone: CBP may not arbitrarily stop vehicles or enter private homes without a warrant or reasonable suspicion. See Almeida-Sanchez v. United States, 413 U.S. 266, 273 (1973) (requiring probable cause or a warrant to search vehicles away from the border in the absence of special circumstances).

Limitations on Detention: Detentions must be reasonable in scope and duration, even within the border zone. See United States v. Martinez-Fuerte, 428 U.S. 543, 566–67 (1976); Montoya de Hernandez, 473 U.S. at 542 (extended detention must be supported by reasonable suspicion or probable cause depending on intrusiveness).

IV. Evidentiary Standard for Investigative Stops by CBP

CBP must meet constitutional standards when initiating investigative stops:

Reasonable Suspicion for Roving Patrols: Agents must articulate objective facts indicating an immigration violation. In United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, the Supreme Court held that roving patrol stops by Border Patrol agents are unconstitutional unless supported by reasonable suspicion. See United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U.S. 873, 884–85 (1975).

Impermissible Factors: Race or ethnicity alone cannot justify a stop. The Court emphasized that while Mexican ancestry may be a relevant factor, it cannot be the sole basis for reasonable suspicion. Officers may consider contextual factors such as proximity to the border, vehicle characteristics, behavior of the occupants, and time of day. Id. at 885–87.

V. CBP’s Role in Vehicle Stops and Immigration Enforcement

Fixed Checkpoints: Permitted without individualized suspicion, provided stops are brief and consistent in protocol. In United States v. Martinez-Fuerte, the Court upheld interior immigration checkpoints where all vehicles are stopped briefly and systematically, noting that such stops do not require individualized suspicion because the intrusion is minimal and the programmatic purpose is lawful. See United States v. Martinez-Fuerte, 428 U.S. 543, 556–62 (1976).

Roving Patrols: Must be based on reasonable suspicion, and any search requires probable cause or consent. The Court in United States v. Brignoni-Ponce held that roving patrol stops are constitutional only when supported by specific articulable facts giving rise to reasonable suspicion of an immigration violation. See United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U.S. 873, 884–85 (1975).

Local/State Police Limitations: Local officers generally cannot arrest individuals for suspected civil immigration violations unless expressly authorized, such as under a formal agreement pursuant to 8 U.S.C. § 1357(g), commonly referred to as a 287(g) agreement. In Arizona v. United States, the Court held that state laws allowing officers to arrest individuals based solely on possible removability were preempted by federal immigration law. See Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387, 408–10 (2012).

VI. Border Search Authority and Electronic Devices

CBP's border search authority is among the most expansive in federal law and applies not only to immigration enforcement but also to national security, customs violations, and criminal investigations.

Key Legal Points:

No Warrant or Probable Cause Required at the Border

Searches conducted at the international border or its functional equivalent are per se reasonable. See United States v. Ramsey, 431 U.S. 606, 616–19 (1977); Almeida-Sanchez v. United States, 413 U.S. 266, 272–73 (1973).Applies to Both Citizens and Noncitizens

The diminished expectation of privacy applies equally to all individuals. See United States v. Montoya de Hernandez, 473 U.S. 531, 538 (1985); Martinez-Fuerte, 428 U.S. at 561.Electronic Devices Are Subject to Search at the Border:

Manual searches require no suspicion.

Forensic searches typically require reasonable suspicion. See United States v. Cotterman, 709 F.3d 952, 968 (9th Cir. 2013) (en banc); United States v. Cano, 934 F.3d 1002, 1015–16 (9th Cir. 2019); United States v. Touset, 890 F.3d 1227, 1234–35 (11th Cir. 2018).

Device Cloning and Delayed Exploitation Are Permitted

Digital content may be mirrored and retained for later analysis. See Cotterman, 709 F.3d at 957–58; Kolsuz v. United States, 890 F.3d 133, 144–46 (4th Cir. 2018).Regulatory and Policy Basis

8 U.S.C. § 1357(a)(3) permits warrantless searches within a “reasonable distance” of the border.

8 C.F.R. § 287.1 defines this distance as 100 miles.

CBP Directive No. 3340-049A (2018) governs digital searches.

⚠️ Caution!

If you travel internationally, be aware:

All Local Data May Be Searched: Emails, texts, downloads, cached files — anything stored on a device may be accessed.

Cloud Data: Access to cloud-stored content is a legal gray area but may still be viewed if linked through the device.

Encryption: You are not legally obligated to unlock encrypted devices as a U.S. citizen, though refusal may lead to delays or seizure.

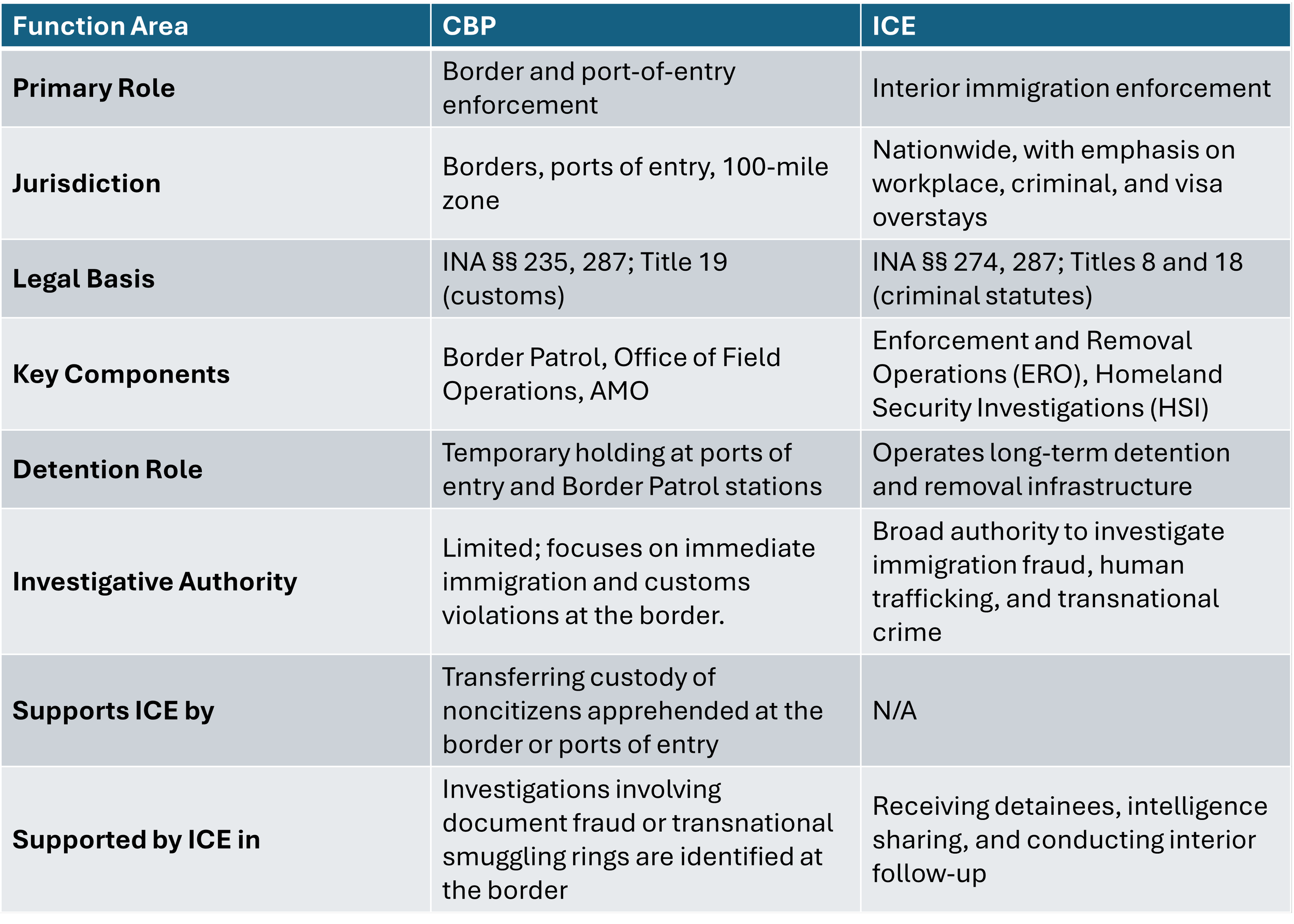

VII. CBP and ICE: Jurisdictional Distinctions and Operational Collaboration

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) are both agencies within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), but they serve distinct and complementary functions in immigration enforcement. Although CBP and ICE share overlapping goals in enforcing immigration law, they function under separate mandates and operational contexts. CBP serves as the first line of defense, while ICE focuses on interior enforcement and complex investigations.Although CBP and ICE share overlapping goals in enforcing immigration law, they function under separate mandates and operational contexts. CBP serves as the first line of defense, while ICE focuses on interior enforcement and complex investigations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): U.S. Customs and Border Protection

What is U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s mission?

CBP secures the border and ports of entry by enforcing immigration, customs, and agricultural laws while facilitating lawful travel and trade.

What is the 100-mile border zone and what can CBP do there?

Federal regulations define a “reasonable distance” from the external boundary—commonly cited as up to 100 air miles—where CBP may conduct certain immigration enforcement activities, including interior checkpoints. Even there, CBP must comply with the Constitution and cannot arbitrarily stop vehicles or enter homes without appropriate legal justification.Can CBP search my phone or laptop at the border?

Yes. Manual device inspections generally do not require suspicion. More intrusive forensic searches typically require at least reasonable suspicion under agency policy and relevant case law.What’s the difference between CBP and ICE?

CBP is the front-line agency at and near the border, operating ports of entry, Border Patrol, and Air and Marine Operations. ICE focuses on interior enforcement, detention, removals, and criminal investigations away from the border.Are immigration checkpoints legal?

Yes. Fixed immigration checkpoints can stop all vehicles briefly without individualized suspicion if operated in a consistent, minimally intrusive manner. Roving patrols away from checkpoints need reasonable suspicion for a stop and probable cause or consent for a search.Can CBP enforce state criminal laws?

No. CBP does not have general police powers to enforce state criminal laws unless a specific federal or intergovernmental authorization applies.Do my constitutional rights apply at the border?

Yes. While the border search exception allows broader inspections, CBP must still act reasonably and respect constitutional limits on searches, seizures, and detention.What should I do if I believe CBP violated my rights?

Document what happened, preserve any paperwork and device logs where possible, and consult an attorney. You can also file a complaint with DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties or the CBP Information Center.

Conclusion

CBP operates under a powerful yet constitutionally bounded set of authorities. While its mission to secure the border justifies certain exceptional powers — especially in border zones and ports of entry — these powers are not without limits. Understanding those limits is essential for travelers, advocates, and legal practitione

Need Help Navigating a CBP Encounter or Enforcement Action?

Whether you’ve had an interaction with CBP, are concerned about your rights at the border, or need strategic legal guidance on immigration enforcement issues, we’re here to help. Schedule a consultation today to speak with an experienced attorney.

Other Helpful Resources:

See Also:

CIL Guide to the Circumvention of Lawful Pathways Rule

CIL Guide to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Directorate